Bureaucracy’s Boundaries

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Editor's Note: This piece has been updated in light of the D.C. Circuit's June 5 ruling refusing to grant the government a stay of the preliminary injunction issued in the Inter-American Foundation litigation.

The federal bureaucracy hosts a range of organizational forms. Some fall completely in the president’s purview: the 15 (for now) cabinet departments, freestanding executive agencies like the Environmental Protection Agency, and executive agencies within cabinet departments such as the Transportation Department’s Federal Aviation Administration. The Supreme Court in late May seems to have pushed independent regulatory commissions and boards like the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) and Merit Systems Protection Board (MSPB) closer to the White House—by barring a lower court order to reinstate their leaders who President Trump fired without cause, despite protections mandated by Congress.

Many organizations exist outside of these cabinet departments, executive agencies, and independent regulatory commissions but retain some tie (weak or strong) to the executive branch—what I termed over a decade ago, bureaucracy at the boundary. There are entities at the border between the federal government and the private sector, such as the U.S. Postal Service and Fannie Mae. There are organizations at the boundary between the federal government and other governments, including those of states, foreign countries, and Native American tribes, such as the National Guard and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. And there are agencies completely within the federal government but largely outside the executive branch, such as the Government Accountability Office (GAO), which is led by someone picked by the president.

The White House is not only exerting more control over independent regulatory commissions such as the NLRB and MSPB but is also coming for these boundary bureaucracies. In March, the so-called Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) physically, with the help of law enforcement, took over the U.S. Institute of Peace (IOP), which Congress created as an independent nonprofit corporation, fired many of its board members, and installed a DOGE underling as its head. The district court on May 19 ruled those actions illegal, finding, among other things, that the IOP does not carry out executive functions. In mid-May, DOGE attempted to install a team inside the GAO, which refused. Facing congressional pressure, the White House (and DOGE) have not pushed the matter, for now, though I wouldn’t put it past President Trump to try firing the comptroller general over impoundment decisions, despite a congressional provision for removal only by a joint resolution of Congress.

Most recently, President Trump claimed to have terminated Kim Sajet, the head of the National Portrait Gallery, part of the Smithsonian, despite the fact that the Smithsonian is a trust instrumentality of the United States, under the direction of the Regents of the Smithsonian, which include leaders from all three branches of government and some private individuals. (At the start of my legal career as an Honors Program attorney in the George W. Bush administration, while I pressed in court that the Smithsonian had sovereign immunity from any attachment of funds related to the giant pandas at the National Zoo, the government’s position was that the unique entity did not fall under direct presidential control.) Sajet would seem to have a good claim against removal, though as of now she has not filed a legal challenge (and is still apparently turning up to work).

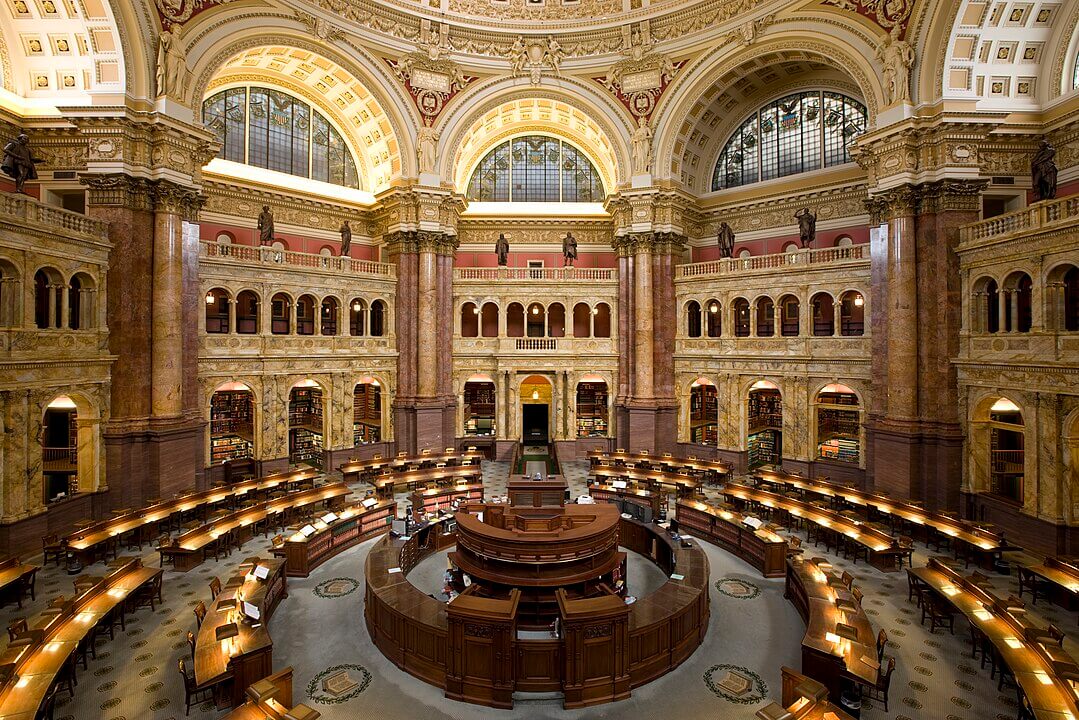

A few days before the GAO refused to open its doors to DOGE, President Trump first fired, by terse email, Carla Hayden, the librarian of Congress, whose 10-year term was to end next year, and then two days later removed the head of the U.S. Copyright Office, Shira Perlmutter, also by email. The White House press secretary claimed about Hayden: “There were quite concerning things that she had done at the Library of Congress in the pursuit of DEI and putting inappropriate books in the library for children.” Of course, the Library takes every published book into its collections, does not check out books, and individuals under 16 cannot enter the building.

Perlmutter, the day before she was removed, issued a third report on copyright and AI, noting, after extensive analysis, that “the Office expects that some uses of copyrighted works for generative AI training will qualify as fair use, and some will not.” (This apparently set off Elon Musk.) The White House then named Todd Blanche, the deputy attorney general, as acting librarian; Brian Nieves, a Department of Justice official, as acting deputy librarian (displacing Robert Newlen, who had become acting librarian following Hayden’s removal under the Library’s regulations); and Paul Perkins, another Justice Department official, as acting director of the Copyright Office.

There are four main legal issues surrounding the White House’s terminations and temporary replacements at the Library of Congress:

- First, a constitutional issue: Can the president fire the librarian of Congress? I think yes, under D.C. Circuit precedent and recent Supreme Court case law on separation of powers.

- Second, also a constitutional issue: Can the president fire the director of the Copyright Office? I think no, under long-standing case law.

- Third, a statutory issue: Can the president use the Federal Vacancies Reform Act of 1998 (Vacancies Act) to name an acting librarian of Congress? I think no, as Congress’s definitions matter for statutory analysis in ways they do not for constitutional claims.

- Fourth, a constitutional issue: Can the president rely on inherent Article II authority to name an acting librarian of Congress? I think no.

I addressed the second and fourth questions previously in the context of the Inter-American Foundation litigation. The analysis is even stronger here against President Trump, given the Library’s more extensive ties to Congress. Just after this piece originally posted, the D.C. Circuit refused to grant the government a stay of the preliminary injunction issued in the Inter-American Foundation litigation, finding it likely that President Trump did not have authority to remove the head, who had been selected by the entity's board of directors and that he lacked authority under Article II to name an acting board member outside the Vacancies Act. I focus here on the first and third issues, while briefly summarizing the earlier analysis for the other questions in this context. In suing over her termination, Perlmutter interestingly has not challenged the firing of the librarian, focusing only on the remaining three issues.

Can the President Fire the Librarian of Congress?

The permissibility of Hayden’s firing rests on the Constitution. Thirteen years ago, the D.C. Circuit addressed the librarian of Congress under the Appointments Clause in Intercollegiate Broadcasting System, Inc. v. Copyright Royalty Board. (I draw here from my earlier writing about this case.) Specifically, the court determined that the judges on the Copyright Royalty Board (CRB) are proper inferior officers if the librarian of Congress, who appoints them, can remove them at will. Although the decision centered on the statutory removal restriction for CRB judges, which the court severed from the statutory scheme, it also critically relied on a determination that the librarian of Congress was a proper head of an executive department who could appoint an inferior officer.

This took some analytical footwork. After all, the Library of Congress is not listed as part of the executive branch in any official classification. Many, including the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel, label the Library of Congress a legislative agency. To reach its holding that the librarian was a proper head of a department under the Appointments Clause, the court reasoned that, while the Library performs some legislative tasks, including housing the Congressional Research Service (CRS), the president’s power to appoint and remove the librarian and the Library’s power to promulgate copyright regulations make it a “‘component of the Executive Branch’” “in this role” (emphasis added). The court had to rely on classifying functions: An agency can, in this view, be an executive department for some purposes but not for others.

Under Intercollegiate Broadcasting, in my view, the president can fire the librarian. And, unlike with the NLRB and MSPB, Congress has imposed no restrictions on the president’s removal power, which a court would have to assess under separation of powers principles. If Congress did not want the White House to have this power, it could restructure the Library, removing its executive functions like copyright rulemaking and adjudication, and change the selection and removal mechanisms. (It made changes to the role of architect of the Capitol after the White House moved too slowly to fire the architect after a scandal in the Biden administration, giving itself power to hire and fire.)

Can the President Fire the Register of Copyrights?

The librarian picks and removes the register of copyrights. As I discussed in April with regard to the Inter-American Foundation, the power to remove follows the power to appoint. As the Supreme Court explained in Free Enterprise Fund v. Public Company Accounting Oversight Board, if Congress vests the appointment of an inferior office in a head of department, “it is ordinarily the department head, rather than the President, who enjoys the power of removal.” Congress can change this default rule but has not done so here. Indeed, the Senate refused to pass a House bill that would have allowed the president to remove the register, with notice to Congress, in President Trump’s first term.

The Justice Department contends that there is an exception to this “power to remove follows the power to appoint” rule—specifically, if the position that appointed the inferior officer is vacant, the president can reach down and fire the lower-level official. But the White House itself has created the circumstances here for that exception by firing the librarian. In addition, there is by regulation an acting librarian, the deputy librarian, who presumably could still select and fire the head of the Copyright Office.

Even if the president cannot remove the head of the Copyright Office, a new librarian could do so, as could a proper acting librarian, making the next two issues salient.

Can the President Name an Acting Librarian Under the Vacancies Act?

Although Perlmutter does not challenge the firing of Hayden in her lawsuit, the White House (through the Justice Department) posits that the answers to the first and third questions—can the president both fire and temporarily replace the librarian—must be the same. Indeed, a Washington Post reporter conflated my answer to the first question with the second inquiry. But a constitutional question often differs from a statutory one.

The Vacancies Act applies to Senate-confirmed positions in “an Executive agency (including the Executive Office of the President, and other than the Government Accountability Office)” but excludes Senate-confirmed roles on “any board, commission, or similar entity that—(A) is composed of multiple members; and (B) governs an independent establishment or Government corporation,” along with a handful of other positions not relevant here. Congress has defined “Executive agency” to mean “an Executive department, a Government corporation, and an independent establishment.” The Library of Congress is clearly not either an “Executive department” or a “Government corporation” as those terms are defined.

But is the Library of Congress “an independent establishment”? Is it “an establishment in the executive branch (other than the United States Postal Service or the Postal Regulatory Commission) which is not an Executive department, military department, Government corporation, or part thereof, or part of an independent establishment” or “the Government Accountability Office”? The argument that the Library is not “an establishment in the executive branch” rests primarily on statutory provisions, mainly that the Library is listed in the U.S. Code under Title 2, “The Congress,” including as part of the “offices and agencies of the legislative branch.” In other statutory provisions, Congress has also listed coverage as including “an independent establishment” and “the Library of Congress,” treating them separately. Similarly, Congress has specified both “Executive agency” and “the Library of Congress” as independent entities in other provisions. It also has designated other agencies, but not the Library of Congress, as independent establishments.

Courts have determined that the Library of Congress does not count as an agency subject to the Administrative Procedure Act and the Freedom of Information Act and that parts of the Rehabilitation Act that are “limited in scope to the executive branch” don’t apply to the Library’s employees.

In addition, the Library of Congress includes the CRS, which “serves as shared staff to congressional committees and Members of Congress” and “assist(s) at every stage of the legislative process,” often confidentially. Before I went to law school, I worked for several months at CRS. Among my tasks, I researched confidential requests from members of Congress. One request from a late member has stuck with me for decades—asking for sources that disputed a well-supported scientific claim (much like asking for sources that say the Earth is flat). I found none and said so. I do wonder how that would play out today if the White House had control over the Congressional Research Service: Would members feel free to ask questions and would CRS staffers feel able to answer them honestly?

Does the Vacancies Act’s treatment of the GAO speak to its coverage (or not) of the Library of Congress? To be sure, Congress did explicitly exclude the GAO from the Vacancies Act, but the definition of independent establishment explicitly includes it, necessitating a carveout. Interestingly, the definition of independent establishment separates “an establishment in the executive branch” and the GAO. To the extent that the Library shares significant similarities with the GAO, the Library seems outside executive branch establishments for statutory purposes. In any event, the Vacancies Act’s silence about the Library does not mean it is included. Given the many statutory considerations and court rulings, I have concluded that the Vacancies Act does not cover the Library of Congress.

In sum, the answer to the constitutional query (can the president remove the librarian) can be different from the answer to the statutory one (does the Vacancies Act apply to the librarian). Justice Antonin Scalia, a lead proponent of the unitary executive theory, actually supported different outcomes to constitutional and statutory questions. In his solo dissent in Mistretta v. United States, where the Court upheld the constitutionality of the U.S. Sentencing Commission, an entity Congress placed in the judicial branch, he wrote: “I am sure that Congress can divide up the Government any way it wishes, and employ whatever terminology it desires, for nonconstitutional purposes—for example, perhaps the statutory designation that the Commission is ‘within the Judicial Branch’ places it outside the coverage of certain laws which say they are inapplicable to that Branch, such as the Freedom of Information Act. For such statutory purposes, Congress can define the term as it pleases.” It appears Congress has done that here for the Library with respect to the Vacancies Act.

Can the President Name an Acting Librarian Under Article II?

If the Vacancies Act does not cover the librarian of Congress, the White House contends that the president can still name an acting librarian under his inherent authority under Article II. If the courts accept that the Vacancies Act applies to the librarian, that would extend the president’s power to one more entity. But if the courts find there is inherent authority to name acting leaders under Article II, that would radically expand executive power.

I addressed this expansive argument in Lawfare earlier, and while that argument has garnered some support by the Office of Legal Counsel, it has recently been rejected in the courts. The district court in Aviel v. Gor, concerning President Trump’s firing of the head of the Inter-American Foundation and the naming of an acting board member (who fired the head as well), issued a preliminary injunction in early April for the plaintiff, finding that the president lacked such power to name temporary board members under the Constitution. In short, the Vacancies Act excludes the board, and the Take Care Clause does not erase the Appointments Clause. Otherwise, as the judge in Aviel v. Gor remarked, “there would be no need for the Recess Appointments Clause.”

Indeed, no court has supported the White House’s position. Even Judge Rao, who dissented from the D.C. Circuit's denial of the stay in the Inter-American Foundation case, noted that "the text and structure of the Constitution strongly suggest the President has no inherent authority to appoint officers of the United States, like IAF Board members, outside the strictures of the Appointments Clause." And the limited scholarship available on the matter opposes it as well. Garrett West, a Yale Law School professor, determined that “the Constitution’s text clearly forbids the President from making temporary appointments without prior congressional authorization.” West draws from the text of the Appointments Clause to show that Congress, not the president, exclusively creates offices and that the president has a mandatory duty to nominate and ask for the Senate’s agreement. And he shows that the two exceptions to the advice-and-consent process in the Constitution—the ability of Congress to place the appointment of inferior officers outside that process and the Recess Appointments Clause—support his conclusion.

Until the past few months, no president has named an acting leader to a principal office outside of the 1998 Vacancies Act (which voids actions by improper acting leaders) or specific statutory provision. The MSPB lacked a quorum from 2017 to 2022. The Department of Justice’s position here (and in the Inter-American Foundation case) would have allowed the White House to fill the empty positions under Article II (the Vacancies Act excludes the MSPB members). But why would Congress impose quorum mandates if the president’s inherent Article II authority could override them?

Status of Litigation and Leadership at the Library of Congress

The district court on May 28 refused to grant Perlmutter a temporary restraining order (TRO), concluding that she had not shown the required irreparable harm needed for such a remedy. The judge noted that the TRO motion “begins and ends with irreparable harm,” and found that her “statutory right to function” claim was not enough, pointing to the Supreme Court’s refusal a few days before to allow fired leaders of the NLRB and MSPB to go back to work while their challenges were litigated. Perlmutter then asked for expedited summary judgment briefing, which the court also denied. The parties turn now to preliminary injunction briefing, which will address the likelihood of success of the merits, which the court has not yet ruled on, in upcoming months.

Members of Congress have resisted the White House’s temporary replacements at the Library—the Democrats more loudly, with the Republicans also quietly pushing back. Newlen, the deputy librarian, appears to be functioning as the acting head. And the White House (and Blanche) are so far keeping some distance.

In the TRO hearing, the judge questioned why Congress had not sued itself, or asked to intervene in Perlmutter’s suit, saying that Congress’s “striking” absence in the litigation undermined Perlmutter’s arguments that the legislative branch’s powers were in danger. Congressional standing in the courts is often tricky as individual members cannot sue to protect institutional interests, notably challenging the constitutionality of a statute. With Republicans controlling the House and Senate, it would seem very unlikely that a chamber would sue. If they did so, however, the chamber would likely have the requisite standing here to challenge at least some of the president’s actions over the Library of Congress. Perhaps individual members could sue over their personal interests in the Library’s functions, such as their use of CRS resources.

Republicans in Congress have almost entirely acquiesced to the new Trump administration. But we are seeing Republican congressional leaders’ resistance to the White House taking over the Library of Congress in this fashion. For instance, Senate Majority Leader John Thune told reporters that they “made it clear that there needs to be a consultation around this—that there are equities that both Article I and Article II branches have [with] the Library of Congress.” I expect one possible outcome is for the White House to nominate (and the Senate to confirm) a new librarian, who could either reinstate Perlmutter or more likely replace her with a new head of the Copyright Office. The government would provide Perlmutter with back pay. And the Library would largely continue to function as it has in the past.